According to Merriam-Webster, “sacred” is defined by the following:

- a. Dedicated or set apart for the service or worship of a deity. b. Devoted exclusively to one service or use.

2. a. Worthy of religious veneration: holy. b. Entitled to reverence and respect.

3. Of or relating to religion, not secular or profane.

O.K. so if we focus only on the first part of Merriam-Webster’s definition, we could say hey, any art is potentially sacred if it is meant be tied in with some type of worship. But, as we see in the second part, the meaning of the definition builds. We see that there’s a holy aspect to it, entitled to reverence and respect. Sacred and holy are kind of synonomous when you think about. And if its going to be holy, it certainly can’t be secular and it definitely can’t be profane.

Sacred art – architecture

Let’s start with some architectural examples of sacred art. Architecture? Yep, architecture. Sacred art applies to paintings, sculptures, stained glass windows and the environment that houses them. In the context of a church, sacred art should be a holistic experience. Take this first example of a Roman Catholic Church that was built in 1950.

Where does your eye gravitate? That’s right, to the main altar where Our Lord reposes in the Tabernacle. And that’s where one’s attention should be in a Catholic Church. It’s not about the priest, it’s certainly not about us, it’s about… well, the guy who established the Church. The Tabernacle in the distance is framed by a gorgeous high altar which is framed by a soaring mural depicting the Beatific Vision. The four evangelists, along with Christ the King, adorn the archway into the altar. The stations of the cross are realistic and reverent – not abstract. Same for the stained glass windows. Altogether, this church offers a holistic experience to visually meditate upon the Sacred Mysteries.

The photo above is a Byzantine-Rite Catholic Church. Visually in terms of both art and architecture, there are some differences between the Roman and the Byzantine rites. But here, like we saw in the Roman-Rite Church, the architecture and the adorning artwork work together to create an atmosphere of visual meditation on the Mysteries of Faith. Note how the mosaic of Mary the Mother of God with the Child Jesus leads visually into the crucifix and then into the icon of Christ the King surrounded by icons of the disciples and key figures from the Old Testament. All of this leads down into the iconostasis where, behind the Royal Doors, Our Lord reposes.

Sacred art – icons

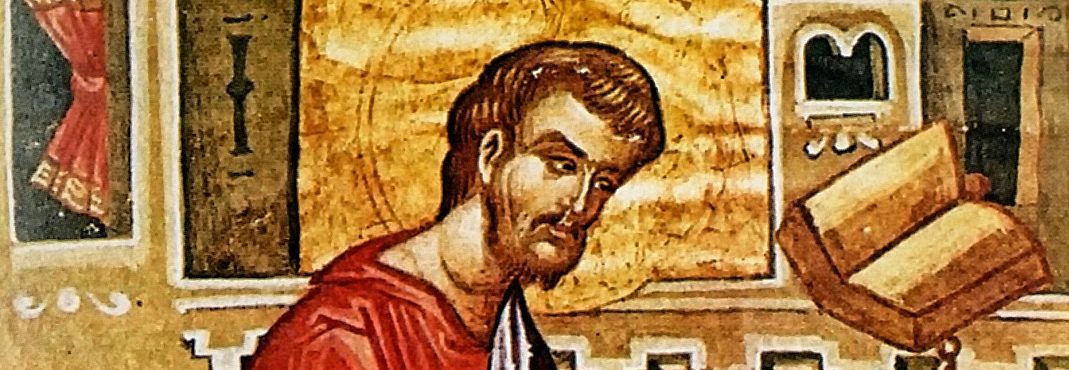

In the early days of Christianity, most of the population was illiterate. From the Roman Empire, to Byzantium and beyond, reading and writing was a luxury for the very privileged, educated few. Not only that but the Bible itself had not yet been composed. Most of the books of the New Testament were still being written. Going to Mass was also a challenge since the Church faced immediate and frequent persecution. So, the Faithful in many circumstances were largely catechized by word of mouth and by visual reference. Enter the icon.

Assuming everyone reading this is familiar with icons like Our Lady of Czestochowa, I’d like to explain what separates an icon from a portrait. In the Book of St. Matthew, chapter 17, Jesus takes Peter, James and John to a mountain and is “transfigured” before them. What they see is Our Lord in a new form. Later, after the Resurrection, He appears “in another shape” to two of the disciples. He’s there in front of them but something has happened. He is not of this world.

Not of this world. Indeed.

When we look at an icon, we’re not looking at a person of this world. The facial expression, the eyes especially, the colors and so much more. If an “icon” is photo-realistic, it is not a true icon. What an icon does is take us out of this world and into the Kingdom of Heaven. We see Our Lord, His Mother, His Angels and Saints in another, non-worldly way. Think of the veneration of icons as looking through a gateway into the Kingdom of Heaven.

Sacred art – paintings

Like the icons of the Eastern Rites, the paintings of the Roman Rite initially served to not only glorify God but also to visualize the Sacred Scriptures to masses of people without the gift of literacy so many of us today take for granted. This next photo is the lower church of the Basilica of St. Francis in Assisi, Italy. The picture really doesn’t do it justice considering the age of the church and how well it has been preserved all of these centuries. Imagine what an incredible visual catechism this was to the people of Umbria in the pre-renaissance era. And… what an equally effective catechism it is to visitors today.

Moving ahead to the 17th Century, look at this painting, The Adoration of the Shepherds by the Dutch painter, Gerard Van Honthorst. This one is an especially interesting and effective work of sacred art because: 1) the people are smiling which was a rare thing to see in artwork of the time – makes sense since this WAS a very joyful occasion. 2) That incredible light source radiating from the Christ Child to Our Lady, St. Joseph and the shepherds. This work of art would be be an ideal visual companion for meditating on the Third Joyful Mystery of the Rosary – The Birth of Our Lord.

And Van Honthorst also used the same style that so captured the joy of the Nativity to also illustrate the sadness of the Passion.

Before the Second Vatican Council, churches were built in the style of the Roman-Rite church I shared above and the interiors often featured tasteful reproductions of sacred art like Van Honthorst’s. I don’t think I need to show the typical suburban American diocesan church built after 1965 so I won’t. Thankfully several of those pre-V2 churches have been preserved and while they may have suffered from bad cosmetics (i.e. those felt banners from the 1970s and the “table altars,”) there is a movement by some to bring back what was lost and under-appreciated. I hope that this site will help in that effort.

Thank you for reading and may God Bless you.

Photo credits (all works of art are public domain unless noted otherwise):

- Roman- and Byzantine-Rite church photos. Taken by Andrew Dunn, St. Luke’s Gallery.

2. Church of the Spilled Blood, St. Petersburg, Russia. By Otto Jula – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=19056854

3. L’altare maggiore della Basilica inferiore di San Francesco (Assisi – Italy). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basilica_of_Saint_Francis_of_Assisi#/media/File:Assisi_Altare_Basilica_inferiore.jpg

4. Adoration of the Shepherds, Gerard van Honthorst, 1622. Wallraf-Richartz Museum, Cologne Germany.

5. The Mocking of Christ, Gerard van Honthorst, 1617. Private Collection.